Category Archives: Jimmies Rustled

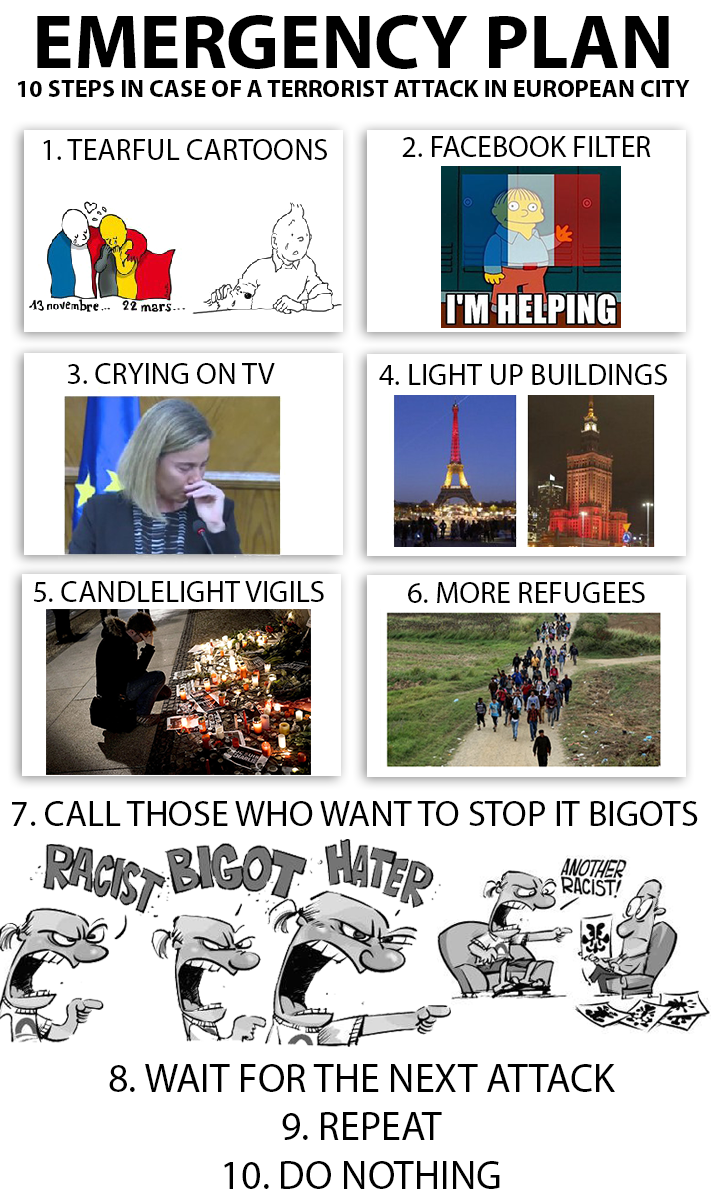

When will European liberal cucks learn?

Turnbull’s Big Election Joke

MSNBC fails to push the racist narrative against trump

Another example of lamestream media bias against trump, massive fail when they interview a black guy at a Trump rally, and hear something they don’t like, and then immediately cut the feed.

52 seconds in

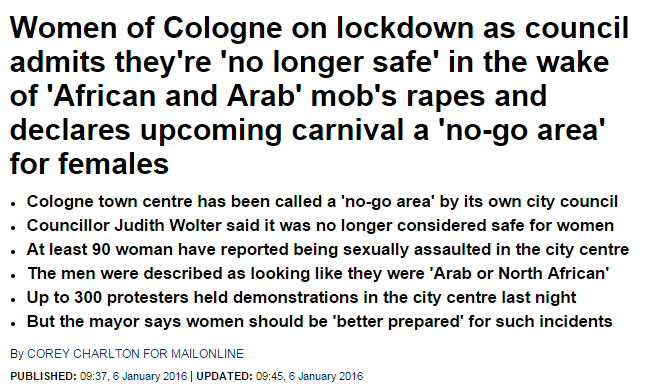

The Rape of Europe

Well that didn’t take long

They aren’t making any more land you know….

Richard Dawkins BTFOs SJWs

Who let these con artist clowns speak at the UN?

Meanwhile, actual women are embarrassed to share their gender with these assclowns.

The Inter-generational War in Australia

Make no mistake, there is an intergenerational war underway in this country right now. And it is asymmetrical warfare. The one side with all the power is doing the attacking, but for the other side it is only just dawning on them that they are under attack. Although it is not going to stay like this forever. Entrenched intergenerational unfairness is the dominant theme that lies across all of the current political issues. Over the coming years these battlelines will crystallise and how we deal with it will reshape Australian politics forever.

The entire economic, political and policy landscape in Australia protects the wealth and power of older people over younger people. And there is a push to enshrine this level of protection further. From housing to higher education, to climate change to communications policy, the whole system is geared against younger people.

Take climate policy for instance. The Abbott government is doing over younger Australians three times over. Firstly it is deferring any costs of mitigating climate change to younger and future generations. Removing a carbon price didn’t reducing the cost burden of climate change action for Australians, it simply removed the cost burden from older Australians and asked younger Australians to pay twice as much to fix it all later. Secondly, along with the mitigation costs being deferred we are also deferring the adaptation costs. We need to invest now to deal with sea level rise, and increases in extreme weather events so we are prepared for a hotter, wilder Australia, but no, we aren’t doing that; younger and future generations bear that cost alone too. And finally by delaying action in Australia and around the world, the younger and future generation bear a magnitude greater impact from climate change than we otherwise should have had to carry.

Housing policy in Australia is another insidious way that older generations selfishly protect their position by hurting those younger than them. The cost of a basic home is two to three times what it cost my parent’s generation. It takes a dual income family to buy what a single income family once could. When it comes to earning an income to pay for housing, the work you do is worth half or less as much what your parent’s income could buy. Requiring both parents to work has massive ramifications for recreation time, the ability to get involved in your community, and naturally, the time you have to parent.

The boom in housing prices has benefited those with their own home, and hurt those without. And the situation has come about not by accident, but by a series of policy decisions that continue to entrench this situation as an unholy status quo. Negative gearing, the ability to get tax concessions for losing money on an investment property, combined with special capital gains tax discounts has fostered the perpetual rise of house prices as a speculative asset rather than a home. It is policy-led asset inflation fed by government via tax deductions. The Reserve Bank recently described it like the rich getting subsidised by the poor. What they really mean is that older home owners are being subsidised by younger non-home owners to inflate the price of owning a home. And when The Greens put out a policy rending the practice of negative gearing, Abbott and Hockey quickly ruled it out and the Labor Shadow Treasurer, Chris Bowen said he doesn’t ever envisage that either party would change the status quo on negative gearing.

It’s not just housing and climate where younger Australia is on the losing side. Pensions that stay ahead of inflation, but unemployment payments that don’t; incentive payments to hire older unemployed Australians but punitive measures such as proposed six-month waiting periods for younger unemployed Australians; free Higher Education for the generation that is currently in power, yet lifetime debts for a student attending university today; the list goes on and on. Even the current debate on debt and deficit has been portrayed by the coalition as about inter-generational equity, yet the only things they have cut to pay down the debt are investments like the NBN that would have benefited younger generations, and programs like youth unemployment programs and spending on education.

In all of these policy areas there is a clear winner and loser across generational lines. The policy positions are being taken for many reasons: the power of the older generations to mobilise to protect their position; the weakness and lack of organisation among younger Australians; and the age of politicians themselves and the circles they move in. The housing scenario is one of the clearest possible pictures of a government defending the indefensible despite all the evidence to the contrary.

How are young people responding? Mostly they are not. But among some there is a residual seething anger. I have seen this type of anger in many types of policy debates. It is the anger of someone who sees fundamental and personal unfairness but has no agency or power to respond. The main response is venting on social media. Snark, cynicism, hyperbole is how people deal with it. The phrase “kill all boomers” is used jokingly by a generation that feels it has had control of own destiny stolen by its elders.

There is no younger people movement. There is no specific organisation, lobby group or think tank that agitates over this. There is no figure head. No one running younger people marginal seat political campaigns. But this will change.

The Australian Youth Climate Coalition has made a good start pushing into the national climate debate but younger people’s explicit representation will go further. All it takes to create a specific group is some leadership and a benefactor or two. It’s been done before on single issue campaigns and this can be done too. There is no reason why a group solely represent younger and future generations can’t be established here in Australia. And my goodness what an impact it could make. Without a specific vested interested groups acting throughout politics defending the interests of younger Australians then they will always lose.

Australian politics will be shaped by these inter-generational wars for the next few decades. The policy fights will get more desperate over time as the wealth and opportunity gap between older and younger grows increasingly clear. I foresee three different scenarios in how this could play out.

A good result would be that new inter-generational compact is created. We have done this before between labour and capital with the Accord and we can do it again across generational lines. We need to sit down together across the generations and rewrite the laws and policies for them to be fairer for all. For this to happen there needs to be a rise in power and organisation in younger people and for older generations to accept that the status quo is unfair. A Cabinet Minister for Inter-Generational Equity could guide the policy process. Between Treasury and the Productivity Commission we have the policy skills to re-shape the current framework. It’s not a lack of expertise that is holding us back from redressing intergenerational equity.

Another potential scenario to play out could be a reshaping of the political landscape where parties would be forced to shape their policies explicitly around inter-generation equity. Instead of a labour versus capital political divide where one party supports the bosses and the other support the workers, you could see parties divide sharply down generational lines. No party currently explicitly accepts the system generational divide although the Greens are the closest to do so. You see segmented generational marketing already at election time from all parties and soon you will see segmented policy development. If the Greens don’t actively embrace a generational approach then they risk the development of a new political force exclusively focussed on generational fairness. The ability of Palmer to set up a successful insurgent political campaign from scratch shows this is possible.

The final potential scenario and maybe the most likely one is that of conflict; a scenario where those in older generations actively maintain their power over the major party policy positions despite deepening inequity. If the status quo remains then some, but not all, of the younger generation will increasingly lash out. You see it now with online gybes and occasional climate-led civil disobedience, but as their future gets further stolen from them expect this only to escalate. The civil disobedience movement will only spread. It is a logical and rational response to a disempowerment that locks in existential threats. It will escalate in frequency but also in fervour. The underlying generational angst will turn into open and public contempt in a level not seen in Australia since the anti-conscription debate of WWI. But it can be resolved before then.

By writing this piece I wanted to draw attention to the underlying thread of intergenerational unfairness that runs through all our current political debates. The future of this country is one of entrenched division and inequity if we don’t recognise this and we don’t fix it now. There are two things that we can do right now to turn it around. Firstly, somehow, we need to establish an organisation that solely, looks at, argues for and mobilises over inter-generational fairness issues. Without this, the unfair status quo will always win. And secondly, people who care about this need to start arguing for the development of a new intergenerational compact. We all need to be talking about what a fair future for all would actually look like.

Australia – Land of the Lie

If you want to a grand spectacle of over-regulation, under-regulation and bald faced lies told to a populace on a daily basis, come to Australia. You can marvel as the peeps you meet bend over and take it, or just open wide and swallow with the meekest of reactions. Humorous, given its reputation. As John Oliver recently described Australia, “Not just the country where Russell Crowe lives, but very much the Russell Crowe of countries.”

Vegans always shitting up everything

Tony Abbott’s Plan to Tackle Housing Affordability

Wind Commissioner

Australia – a very high taxing country

Repost of an excellent article from the AFR.

No matter how you dice the numbers, Australians pay high taxes – but they are not better governed as a result

Whichever way you look at it, our taxes are high.They are high by historic standards. Fifty years ago, taxes were about $5000 per person after adjusting for inflation. This grew to around $8000 per person by the mid‑1970s, $11,000 by the mid‑1980s, $12,000 by the mid‑1990s and $17,000 by the mid‑2000s. Today the tax burden is around $19,000 per person, still allowing for inflation.

Even if the tax burden had grown in line with growth in wages and the economy, it would only be $13,000 per person. Those bleating about crashing revenues are on another planet. Their complaint, in essence, is that taxes ought to grow even faster.

There is no justification for the ever-expanding tax burden. Living standards for all groups of society have risen over the last 50 years, which means the need for government welfare services has declined. And we haven’t uncovered new forms of effective government intervention either. To the contrary, the prosperity‑promoting effects of free markets and the many failings of government involvement have been demonstrated time and again.

Yet the growth of tax is unwavering, supported by the fact that its collection over the decades has become both hidden and automatic, a development euphemistically known as “tax efficiency”.

Our taxes are also high by international standards. The Coalition, Labor and the Greens will tell you that Australia’s tax burden is about 28 per cent of GDP, compared with an OECD average of about 34 per cent. This is a con job using dodgy statistics.

The 34 per cent figure is a simple average that puts the same weight on each of the 34 countries of the OECD. Thus high‑taxing Iceland has as much impact on the average as the lower‑taxing United States, even though the US’s population is 1000 times bigger than Iceland’s.

If you properly account for the different sizes of the OECD countries, the average tax burden in the OECD comes out at 30 per cent of GDP.

What’s more, this weighted average for the OECD is bumped up by the inclusion of “social security” or “national insurance” contributions present in most countries of the OECD except Australia –while the tax burden figure for Australia is artificially kept down by the exclusion of superannuation guarantee payments.

If superannuation guarantee payments are excluded, then at least some of the social security contributions in other countries should be excluded too. After all, both are compulsory, they add to the individual payer’s retirement income, and their preservation for retirement is similarly subject to significant government manipulation and pilfering.

Once we exclude both from the calculations, the weighted average tax burden in the OECD falls to 22 per cent of GDP, while Australia’s tax burden remains at 28 per cent of GDP. And even if we exclude only half of the social security contributions on the grounds that only half of them resemble Australia’s superannuation guarantee payments, the OECD average tax burden would still be lower than Australia’s tax burden.

HIGH-TAX COUNTRY

Another way to compare tax burdens in a fair way is to include both superannuation guarantee payments and social security contributions in the calculations. Under this approach, the weighted average tax burden in the OECD is 30 per cent of GDP, while Australia’s tax burden rises to 31 per cent of GDP.

So no matter which way you look at it, Australia is a high tax country, even by OECD standards.

But we shouldn’t be comparing ourselves to the debt-ridden, stagnant basket cases of the old world. If we want to be more prosperous, we should compare ourselves with the richest and most dynamic countries in the world.

There are four non-OECD countries that are richer than us — Singapore, Hong Kong, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. We compete with each of these for investment, skilled workers and entrepreneurs, and each country has a markedly lower tax burden than Australia. The tax burden in Singapore and Hong Kong is about14 per cent of GDP, and even lower in Qatar and the UAE.

The Coalition, Labor and the Greens will tell you again and again that our taxes are low. Every time this lie is repeated, it needs to be refuted. And in this task, I’m happy to be a broken record.